By Sean Carleton

On September 30, 2020, the RCMP sent out a tweet to mark Orange Shirt Day. The tweet contained a photograph of RCMP employees wearing orange to recognize IRS Survivors. It was accompanied by a message that read: “Today, RCMP employees are wearing orange to honour and remember the Indigenous children who were sent away to Residential Schools. Take this day to reflect on the past, recognize our role, and start the conversation.”

The RCMP was roundly criticized for its tweet. In particular, the message’s use of passive voice – to say that children “were sent away” – hides the RCMP’s active role in working with church and state officials to remove Indigenous children, often by force, from their communities.

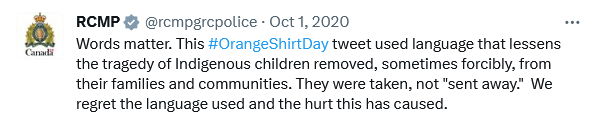

Given the overwhelmingly negative response to the tweet, the RCMP issued a corrective tweet the next day, on October 1, 2020. It noted that “words matter” and “we regret the language used.” The RCMP’s new tweet, however, still used passive voice and further obscured the force’s direct role in the system. The tweet acknowledged that children “were taken” but it does not make clear that the RCMP often carried out the apprehensions.

What was the role of the RCMP in the Indian Residential School system?

This recent controversy highlights the need for greater public awareness about the RCMP’s role in residential schooling. This short primer begins to fill that gap.

Over the past three decades, sparked by Survivors coming forward and sharing truths about their IRS experiences, historians have published a number of studies about Canada’s Indian Residential School system. Peer-reviewed books and articles by scholars have documented how church and state officials collaborated to devise, deploy, and defend a genocidal school system for over one hundred years (between the 1880s and 1990s). The intent was to attack, undermine, and delegitimize Indigenous lifeways to facilitate assimilation and support settler capitalist development and Canadian nation-building.

Missing from the historical literature, though, is a detailed examination of the role of police in enforcing the IRS system, though newer scholarship by myself and other scholars is starting to investigate such connections.

The most in-depth account of the RCMP’s role in residential schooling actually comes from a 2011 report written by Marcel-Eugène LeBeuf, a civilian member of the RCMP, “on behalf of the RCMP.”

According to the RCMP’s website, the report’s main findings are:

There was a lack of trust between Indigenous Peoples and the RCMP.

Many former students claimed they learned to fear the RCMP over the years. As a result, many didn’t try to contact police.

The RCMP were mostly present at Indian Residential Schools as “truant officers”.

When requested, the RCMP:

- searched for and returned truants

- fined parents whose children did not go to school

The RCMP assisted Indian Agents with the removal of children from their homes.

The police helped Indian Agents bring children to schools, sometimes forcibly.

RCMP members developed positive relationships with Indigenous youth.

RCMP officers got involved in activities beyond their traditional role, such as music and sports.

The RCMP did not know of the majority of abuse happening within the schools.

During the interview process, many former students confirmed that the RCMP could not know about the abuse.

Neither the students nor the school would have told them of these occurrences.

In sum, the report acknowledges RCMP involvement in the IRS system but, like the 2020 Orange Shirt Day tweets, it downplays the force’s direct complicity. Once again, the RCMP use passive voice to present the force’s involvement as marginal while shifting blame solely to the government.

The RCMP website begins its explanation of the report in such a manner:

Indian Residential Schools and the RCMP

For more than a century, the Canadian government removed 150,000 Indigenous children from their families and communities to attend government funded Residential Schools.

In 2011, the RCMP released a report titled “The Role of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police during the Indian Residential School system”.

“When requested,” the RCMP concludes, its members just did their job of enforcing the laws and policies the government created.

Closer scrutiny of the report and the evidence used yields a different assessment. Though it is true that churches and government operated and funded the system, the police actively enforced it. The system needed the police to function. It is thus more accurate to say that a church-government-police partnership developed by the late 1800s and early 1900s that was crucial for maintaining the system’s power over Indigenous Peoples. All parties played different but mutually reinforcing roles in residential schooling.

In terms of the RCMP’s role, I will now outline three ways it helped enforce the IRS system.

The RCMP captured absentees, returned run-aways, and fined parents

In the late 1800s, the Department of Indian Affairs created Indian agents responsible for the local management of “Indian Affairs” in agencies across the country. The Indian agent’s job was to enforce the government’s Indian policies on the ground. Starting in the 1890s, the federal government created policies making attendance at “Indian” schools compulsory, and Indian agents often recruited Mounties to assist them and church officials in persuading parents to send their children. Where parents and guardians refused or resisted new attendance policies, preferring to educate their own children on the land as they had since time immemorial, the RCMP were used to coerce attendance at church-run and government-funded schools by the early 1900s.

In 1920, the government amended the Indian Act to make attendance at Indian schools mandatory. Police, and in particular the RCMP, now more frequently acted as truant officers for the IRS system. They captured absentees, returned run-away students, and fined and/or arrested Indigenous parents who refused or resisted. When Indian agents enlisted the services of the police, it often came at a cost. The RCMP did not carry out these extra duties for free; the force billed the DIA for additional expenses related to their work as truant officers. By the 1940s, the cost of using the force in this way became so burdensome that the DIA asked Indian agents and IRS principals to take on the work of returning run-aways themselves to save money. The RCMP thus benefited financially from their IRS work which diverted necessary funds from the DIA budget that could have gone to addressing the myriad problems with the system.

Finally, while the RCMP’s report denies any awareness of the rampant abuse and mistreatment of children happening at many schools, the evidence suggests this is unlikely. When, for example, the Thunderchild Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan burned in 1948, the RCMP became singularly focused on catching the culprits and criminalizing them rather than investigating the notoriously bad conditions at the school – frequently raised by community members on the Thunderchild reserve – to determine why children would burn down school.

RCMP indifference claimed children’s lives

Countless other records exist where, in the face of much suffering and obvious concern for children’s wellbeing in schools across the country, police dismissed or discredited Indigenous students and parents, choosing instead to punish so-called “troublemakers.” Far from being reluctant or even neutral actors, the RCMP most often sided with Indian agents and school officials and worked hard to enforce the system as part of its overall effort to serve and protect Canada’s settler capitalist status quo.

Any attempt to understand the RCMP’s more complicated history must thus include reckoning with the police’s involvement in enforcing the IRS system.

Sean Carleton is a historian in the departments of history and Indigenous studies at the University of Manitoba.