By Alex Williams

The pass system was a nearly 60-year system of segregation, beginning in 1885 and enforced on First Nations by the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP), the Royal North-West Mounted Police (RNWMP) and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), in concert with the Department of Indian Affairs. The system was deployed throughout treaty areas 4, 6, and 7, but mobility restrictions similar to the pass system have been reported in areas throughout the country.

The system required First Nations people to request permission to leave the confines of their reserve, and if granted, to carry a pass, which indicated their destination, purpose, and length of time they would be absent. Applied at the pleasure of the Indian Agent, the pass system’s impacts were multiple and incalculable, and its legacies can be seen in current-day statistics of incarceration, poverty, health, education, and other impacts.

Prime Minister John A. Macdonald implemented the segregationist system at the close of the Northwest Resistance with zeal, saying it was “in the highest degree desirable to adopt it.” 1 Macdonald’s goal was to deter Indigenous people from entering white towns and cities without permission:

As respects Indians encamping in towns and villages, the Supt. Genl. is of opinion that the sites of such places may be regarded as the property of the Municipalities or Authorities of said Towns and Villages and therefore as included in those properties, from which under the Treaty the Indians are prohibited from entering upon without permission. The Mounted Police, therefore, or Municipal Officers should be instructed to insist upon all Indians camping within the limits of Town sites or Villages producing permits from the Indian Agents showing what their purpose in camping in the vicinity its and for what length of time the permits have been granted them. Should they fail to produce such permits, they should be compelled to leave the precincts of said Towns or Villages.2

Macdonald knew however that the system was illegal and acknowledged this by saying, “should resistance be offered on the ground of Treaty rights the obtaining of a pass should not be insisted upon.” 3

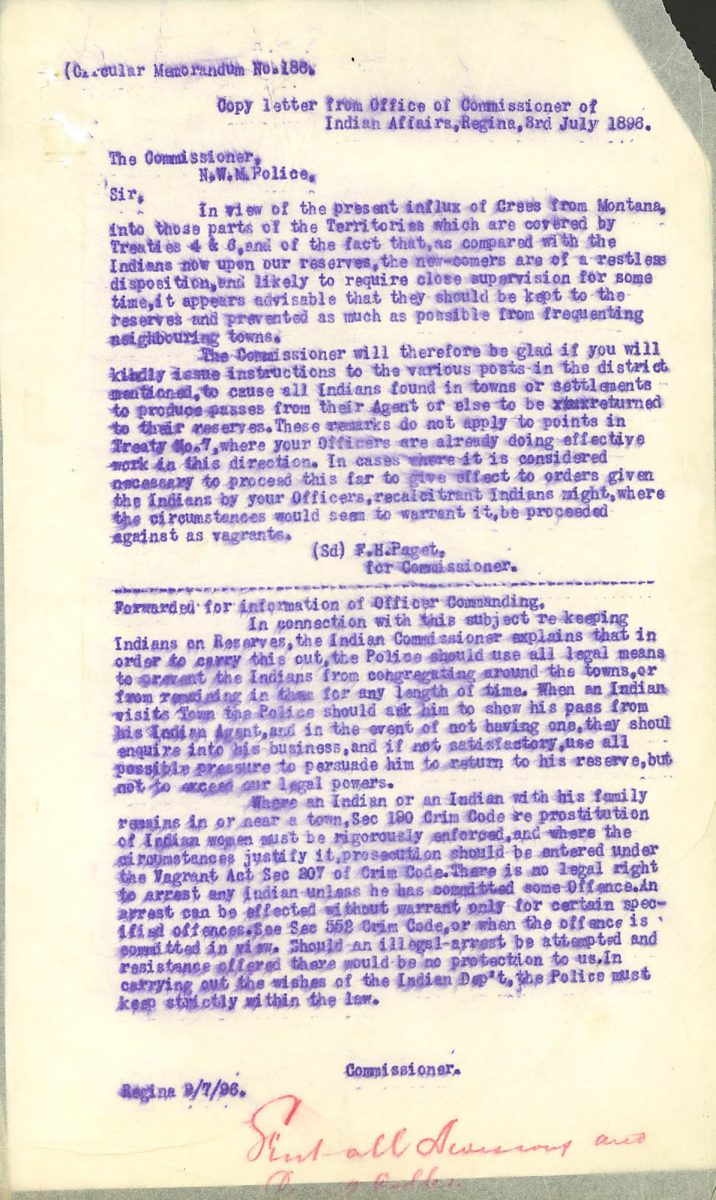

In 1893, Commissioner Lawrence Herchmer ordered the Force to end enforcement of the system, as it lacked any basis in law. However, under pressure from Indian Commissioner Hayter Reed, the architect of the system, Herchmer resumed enforcement of the practice. Herchmer’s subsequent 1896 circular to Force members outlined how the NWMP was to use the Criminal Code to disingenuously charge people with vagrancy and prostitution, since they had no legal way to charge people for violations of the pass system:

When an Indian visits a town, the Police should ask him to show his pass from his Indian agent, and in the event of not having one, they should enquire into his business, and if not satisfactory, use all possible pressure to persuade him to return to his reserve, but not to exceed our legal powers. Where an Indian or an Indian with his family remains in or near a town, Section 190 of the Criminal Code re. prostitution of Indian women must be rigorously enforced, and where the circumstances justify it, prosecution should be entered under the Vagrant Act, Section 207 of the Criminal Code. Should an illegal arrest be attempted and resistance offered there would be no protection to us. In carrying out the wishes of the Indian Department, the Police must keep strictly within the law.4

The pass system worked in concert with other policies intended to buttress each other, for example access to one’s children in residential school required a pass for the parents to visit, access to rations required obedient compliance with the terms of a pass, farm instructors could restrict access if they felt people should be farming rather than travelling, or simply to reinforce an idea of authority over Indigenous people that they did not have.

The Pass System on Vimeo.

Some commentators have suggested that the system had little impact, at times without reference, 5 or by relying on a patchwork of extant archival sources available at the time, and no corroborating oral history from the communities affected.6 This testimony is crucial because in the 1960s, the Department of Indian Affairs shut down the Indian Agency system and ordered a massive purge of documents from Indian Agencies. 7 Destroyed in burn piles, many may have related to the pass system’s implementation. Important documents that remain, however, are often in regional archives. These point to a system that has a much broader application and impact than previously asserted and was corroborated by Elder testimony in communities.8

These impacts are also observable in the non-Indigenous population, who, by escaping these consequences of the pass system, headed on a divergent path from First Nations – one that led to prosperity, safety, and the security of their assumed domain over territory that remains in the settler imagination.

The enforced absence of Indigenous people also allowed for the establishment of settler infrastructure (without the pretence of modern-day consultations), thereby cementing an idea of unfettered settler predominance over territories that were intended by Treaty to be shared. In fact, enforcement of the pass system was also actively encouraged by the settler population and the press.9 The powerful normalization of the segregationist practice, and its enforcement by the RCMP, had lasting and pervasive impacts on Indigenous and Canadian relations.

Directed by Tasha Hubbard, nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand Up, weaves a profound narrative encompassing the filmmaker’s own adoption, the stark history of colonialism on the Prairies, and a vision of a future where Indigenous children can live safely on their homelands.

- John A. Macdonald to Edgar Dewdney, October 28, 1885, Record Group 18, volume 3710, part 3, file 19, 550-3, Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, Ontario

- Macdonald, 550-3.

- Macdonald, 550-3.

- NWMP Circular Memorandum 186, July 9, 1896 to NWMP Members, Record Group 18, volume l354, part 3, file 76, Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, Ontario.

- Patrice A. Dutil, Prime Ministerial Power in Canada : Its Origins Under Macdonald, Laurier, and Borden, (Vancouver, UBC Press, 2017), p. 72.

- F. Laurie Barron, “The Indian Pass System and the Canadian West”, Prairie Forum 13, no. 1, (1988): 25.

- Joanna Smith, “Ottawa acknowledges some records of pass system were destroyed before historical value known,” Toronto Star, April 27, 2016. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2016/04/27/ottawa-acknowledges-some-records-of-pass-system-were-destroyed-before-historical-value-known.html (Accessed May 20, 2023).

- The Pass System, directed and researched by Alex Williams (2015; Toronto, ON: Vtape), https://vimeo.com/ondemand/thepasssystemfilm

- Barron, 33.