By Shiri Pasternak and Tim Groves

Canada authorized several high arctic relocations of Inuit people that exposed them to indefensible conditions of starvation and loss. But they could not have done so without the support of the RCMP. Nor could they have taken so many children to Residential Schools without the use of the RCMP in the north or implemented the Eskimo Disc Number system.

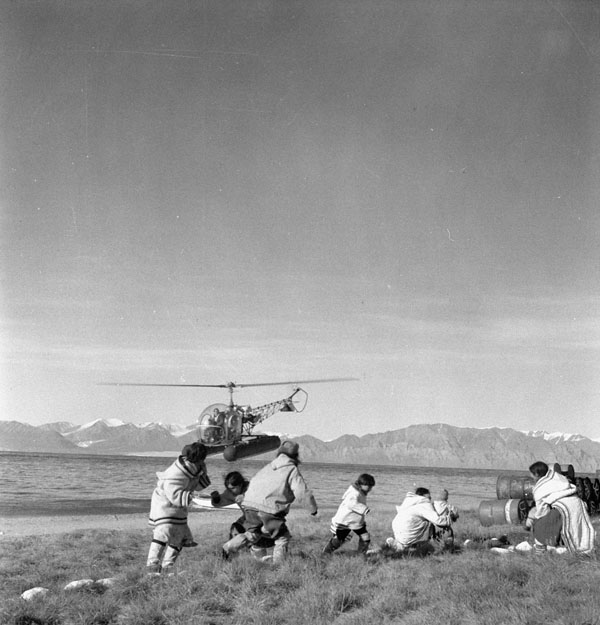

Moved like chess pieces on a board

The first relocation was at the behest of the Hudson’s Bay Company, in 1936, with the support of the federal government. Fifty-three Inuit were moved from their homes in Cape Dorset, Pangnirtung and Pond Inlet to Devon Island.

The removal of Inuit made room for commercial fishing enterprises but mostly for army stations. Canada used the Inuit to assert their sovereignty through these relocations, tearing Inuit away from their homelands in the process.

For example, one relocation was made in 1949 in Ennadai Lake where the military built a radio station. Around 50 Inuit were relocated to nearby Nueltin Lake and told they were being moved further north because the government had fears they would become too dependent on southern supplies. This, despite providing for themselves for centuries from caribou and a multitude of other food sources. Elder Job Muqyunnik told an interviewer about this time:

“That was the hardest time of my life because we didn’t have anything to survive with anymore.”

The next series of relocations took place in the 1950s when the federal government relocated Inuit from their villages and settlements on the eastern side of Hudson Bay to Grise Fiord and Resolute Bay in the High Arctic, a much harsher and colder environment than where they came from, that they did not know well, and where hunting or fishing opportunities were scarce.

The federal government also relocated Inuit in Quebec from Inukjuak who were accustomed to brushy vegetation and freshwater lakes. For Minnie Allakariallak, “It was like a desert, just gravel,” she remembered. The landing site was “just basically bare rock.” They had been told there was a much better wildlife landscape in the north, but instead encountered a more difficult and unknown environment.

RCMP intimidation, coercion, and control

The RCMP played a central role in these relocations. Many Inuit described the compulsion they felt when intimidated by RCMP officers who insisted they must relocate. They approached people individually rather than as a community in Inukjuak, often through interpreters, sometimes making repeat visits.

As this story of intimidation portends, the RCMP were more than a police force in the North. They were a form of government. As the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) described:

For many years, government administration in the Arctic took the form of the local RCMP detachment. Professor Williamson [Department of Anthropology, University of Saskatchewan] has observed that the RCMP held the power of the law and, in the isolated Arctic, held that power without the checks and controls that exist in a society of equals, such as among non-Inuit in southern Canada. The RCMP were seen as having extraordinary legal power and an extraordinary reputation for being able to deliver the results of this legal power. Anything they said would be treated with respect and considered inordinately carefully. The most mild inquiry from an RCMP member would carry much more weight than it would in the south. For decades, continuing into the 1950s, the RCMP were the “embodiment and custodians of Canadian Government policy” and carried out almost every government function, from handing out family allowances to enforcing the law in the Arctic.

They operated an informal “pass system,” like they did in the prairie provinces, controlling the movement of the Inuit between villages in the relocation sites. For example, RCMP Cst. Pilot, stationed at Grise Fiord, warned that if one moved from the settlement, others would follow. He led an initiative to advise the Department to write to the Inuit and discourage any movement from their relocation sites.

The RCMP also managed the “welfare” of the Inuit during these relocations, in effect turning the new colonies into “reformatory camps.” They often exercised their power in order to imbue what they saw as positive values, like hard work and reverence for White Man’s Law. For example, they used their powers to criminalize Inuit for stealing food, even though the Inuit’s starvation was a result of the federal government’s relocation policy.

One incident was recorded at Henik Lake of three Ahiarmiut hunters and one young man arrested for “Breaking, Entering and Theft.” While awaiting the arrival of the Territorial Court, they were doubly punished by being forced to break rocks. One of the hunters was blinded when a rock splinter entered his eye.

Archives / Collections and Fonds

The RCMP were not just enforcing law, they were also part of the overall decision-making process for the relocations. The relocations were essentially coordinated between the Department and the RCMP, whose detachments were established already in the High Arctic. It was the RCMP that informed Commissioner Nicholson of their idea to move Inuit families to Craig Harbour, Cape Sabine and Dundas Harbour, as Insp. Larsen recommended, “where colonization by them appears to be suitable and feasible.” At the Special Committee on Eskimo Affairs meeting in 1952, Larsen’s plan was discussed and a policy of relocation developed by the federal government accorded with his recommendations.

Inuit forced from their lands in the 1950s filed a claim against the federal government and eventually won compensation.

RCMP, Inuit, and Residential Schools

The 1960s saw the establishment of residential schools in the North. This separation, Inuk writer Norma Dunning writes, seemed “inconceivable” to Inuit parents. That’s because “[t]he parents were always the people responsible to teach their child how to survive on the tundra and how to be a good person.”

Dunning shows that police reports tell of families of Inuit children camping in tents around the school, waiting for them to complete their days. The RCMP “considered charging families with loitering while pointing out that the Inuit mother would be the most reluctant to give her child over to a school system and the most problematic person in the situation.” Criminalizing mothers who badly missed their children was a pretty grim choice for RCMP to make.

It seemed that in some cases, even the RCMP questioned their own authority to take children away from their families. As the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) report notes, “Another RCMP report from that year [1941] questioned whether the force should be acting as truant officers.”

However, that didn’t stop them from playing this role, even knowing what destiny lay in store for these children. The TRC report records the story of Eric Anautalik, who explained the “the trauma that he felt as a three-and-a-half-year-old being picked up by an RCMP officer and, in his words, ‘brought into the modern age.’ As he remembers, “I was in shock, I mean I was taken, literally, I was snatched by the policeman from my mother’s arms … In that single day, my whole life changed.”

At the Aklavik Roman Catholic school, the terrorizing experience of residential schools would force students to escape, only to end up back in the hands of the RCMP – the same people who originally took them from their families. As Métis survivor, Angus Lennie tells:

Failing to eat the strange food, making too much noise, or not listening could lead to a student being required to stand on a bench in the corner—a punishment that students found humiliating. Angus felt that he and his fellow students were under constant surveillance. “I learned to live in fear. Fear! To be quiet, listen and follow direction. Soon I was taught ‘not to think for myself’ just ‘listen + do’ and things would be fine.” All the children longed to go home; some tried to make their way back to their families, only to be returned by the RCMP. Parental visits were eagerly anticipated—all too infrequent and short.

The abuse suffered by children in the schools was horrific, as is well documented by the TRC. But the role of the RCMP in separating families, harassing awaiting parents outside the schools, and catching run-aways solidified students’ and parents’ experience of the schools as carceral institutions.

RCMP and the Eskimo Disc Numbers

Concerns about Canadian sovereignty were never disclosed to the Inuit during the relocations. Instead, they were gradually rent from their lands, many never returning to their original homes.

Likewise, the Eskimo Disc Numbers were distributed with little explanation. The RCMP and federal government were opposed to traditional Inuit names, since they did not understand or know how to pronounce them, and objected to them not including surnames. A number of suggestions were put forward on how to resolve this. In 1932, the RCMP began fingerprinting Inuit, but they were dissatisfied with a system that did not allow them to track young children whose fingers were still growing.

In 1935, a medical examiner proposed that an identity disc system be implemented. By 1945, according to research by Derek Smith, the Family Allowance Act of Canada defined an “Eskimo” person as being “one to whom an identification disk has been issued.”

Starting in 1941, the RCMP enforced this dystopian program to force Inuit people to wear an ID disc tag at all times. Rather than bearing their names they were embossed with an identifying number.

The RCMP distributed a small leather disc about the size of a Loonie coin to each person, and instilled fear in people at the prospect of losing them. Used for monitoring and administration, no other group in Canada has been required to have such a number to access basic services. The program applied to Inuit in the Northwest Territories, today’s Nunavut, and Quebec, but it was never administered in Labrador.

The RCMP played a central role, not only in the distribution of the discs, but in maintaining the whole system. As Norma Dunning describes in her book, Kinauvit?: What’s Your Name? The Eskimo Disc System and a Daughter’s Search for her Grandmother is on the Eskimo Identification Tag System:

Because of the physical placement of RCMP posts, RCMP constables were put in charge of the distribution of the discs. They also served as the administrators of the system as they maintained disc lists and reported that information back to Ottawa. They were the enforcers of the disc system.

She interviews elders who describe being fearful of losing their discs. Most people found them dehumanizing. Dunning interviews the important author and Inuit leader Zebedee Nungak who tells her his baptism certificate records his identity as E9-1956. Some accounts include school children being called out by their disc number rather than by their name in school.

Opposition to this dehumanizing system mounted in the 1960s. By 1970 an Inuit community leader, Abraham “Abe” Okpik, was appointed to lead Project Surname: a program to allow people to choose their own names. In 1972, the ID disc tag program was officially discontinued in the Northwest Territories (and today’s Nunavut), and by 1978 it was also discontinued in Quebec. However, some people were still receiving disc numbers into the 1980s.

Continuities of RCMP harm today

The RCMP’s treatment of Inuit continues to be an issue in Nunavut today. For example, the Civilian Review Complaints Commission (CRCC) recently announced it would to review the handling of public complaints by RCMP in Nunavut. This follows a complaint and investigation launched with the CRCC into the conduct of Kinngait (Cape Dorset) RCMP members. These members were involved in an incident where a man was struck by a moving RCMP vehicle. The officers then used force to arrest him. He was then placed in a cell at an RCMP detachment, where he was assaulted in a cell by another detainee, which then required him to be airlifted to an Iqaluit hospital for treatment.